For a network to function and facilitate communication properly, there are three crucial components:

- Mac Addresses

- IP Addresses

- Ports

Together these elements, ensure that data is correctly sent and received between devices across both local and global networks, forming the backbone of seamless network communication.

Mac Addresses¶

A Media Access Control (MAC) address is a unique identifier assigned to the network interface card (NIC) of a device, allowing it to be recognised on a local network. Operating at the Data Link Layer (Layer 2) of the OSI model, the MAC address is crucial for communication within a local network segment, ensuring that data reaches the correct physical device.

Each MAC address is 48-bits long, and typically represented in hexadecimal format, appearing as six pairs of hexadecimal digits separated by colons or hyphens.

Example:¶

00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E

The uniqueness of a MAC address comes from its structure, the first 24 bits represent the Organisationally Unique Identifer (OUI) assigned to the manufacturer, while the remaining 24 bits are specific to the individual device. This design ensures that every MAC address is globally unique, allowing devices worldwide to communicate without address conflicts.

Note: The windows GETMAC command will return the MAC address of every network interface card on the host

How MAC Addresses are Used in Network Communications¶

MAC addresses are fundamental for local communication within a local area network (LAN), as they are used to deliver data frames to the correct physical device. When a device sends data, it encapsulates the information in a frame containing the destination MAC address; network switches then use this address to forward the frame to the appropriate port.

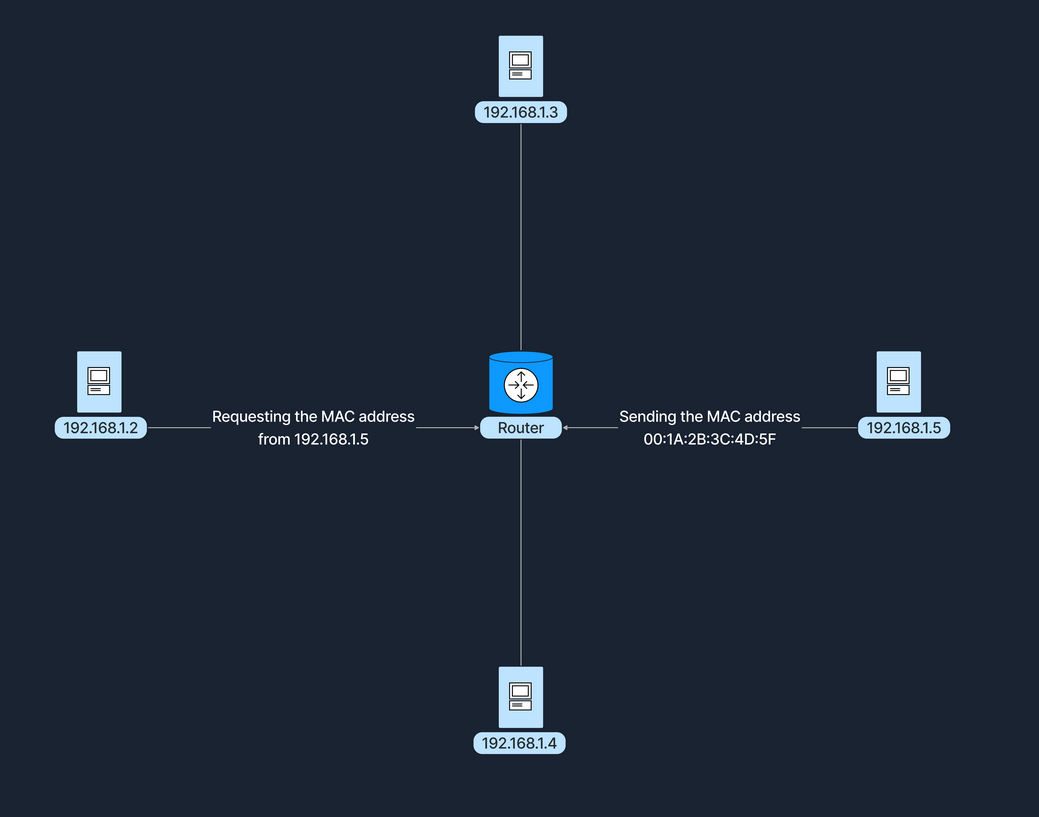

Additionally the Address Resolution Protocol plays a crucial role by mapping IP addresses to MAC addresses, allowing devices to find the MAC address associated with a known IP address within same network. This mapping is bridging the gap between logical IP addressing and physical hardware addressing within the LAN.

Example:¶

Imagine two computers:

- Computer A (with an IP address of 192.168.1.2)

- Computer B (with an IP address of 192.168.1.5)

Both are connected to the same network switch. Their MAC addresses are:

- Computer A has the MAC address of 00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E

- Computer A has the MAC address of 00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5F

When Computer A wants to send data to Computer B it first uses the Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) to discover Computer B's MAC address associated with its IP address.

After obtaining this information, Computer A sends a data frame with the destination MAC address set to 00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5F.

The switch receives this frame and forwards it to the specific port where Computer B is connected, ensuring that the data reaches the correct device.

Example showing router using ARP

IP Addresses¶

What is an IP Address?¶

An Internet Protocol (IP) address is a numerical label assigned to each device connected to a network that utilises the Internet Protocol for communication.

Functioning at the Network Layer (Layer 3) of the OSI model, IP addresses enable devices to locate and communicate with each other and across various networks.

There are two versions of IP addresses:

- IPv4

- IPv6

IPv4 addresses consist of 32-bit address space, typically formatted as four decimal numbers separated by dots, such as 192.168.1.1. In contrast to IPv6 addresses which were developed to address the depletion of IPv4 addresses, have a 128-bit address space and are formatted in eight groups of four hexadecimal digits

Example:¶

2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

How IP Addresses are Used in Network Communication¶

Routers use IP addresses to determine the optimal path for data to reach its intended destination across interconnected networks.

Unlike MAC addresses, which are permanently tied to the devices network interface card, IP addresses are more flexible; they can change and are assigned based on the network topology and policies.

Ports¶

A Port is a number assigned to specific processes or services on a network to help computers sort and direct network traffic correctly.

It functions at the Transport Layer (Layer 4) of the OSI model and works with protocols such as TCP and UDP. Ports facilitate the simultaneous operation of multiple network services on a single IP address by differentiating traffic intended for different applications.

When a client application initiates a connection, it specifies the destination port number corresponding to the desired service.

Client applications are those who request data or services, while server applications response to those requests and provide the data or services.

The operating system then directs the incoming traffic to the correct application based on this port number. Consider a simple example where a user accesses a website: the user's browser initiates a connection to the server's IP address on port 80, which is designated for HTTP.

The server, listening on this port, responds to the request. If the user needs to access a secure site, the browser instead connects to port 443, the standard for HTTPS, ensuring secure communication.

Port numbers range from 0 to 65535 and it is divided into three main categories, each serving a specific function.

Note: Using the netstat tool to view active connections and listening ports.

Well-Known Ports (0-1023)¶

Well-Known Ports numbered from 0 to 1023, are reserved for common and universally recognised services and protocols as standardised and managed by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).

For instance, HTTP, which is the foundation of data communication for the World Wide Web, uses port 80, although browsers typically do not display this port number to simplify the user experience. Similarly, HTTPS uses port 443 for secure communications over networks, and this port is also generally not displayed by browsers. FTP, is another protocol that facilitates file transfers between clients and servers, using ports 20 and 21.

Registered Ports (1024-49151)¶

Registered Ports which range from 1024 to 49151, are not strictly regulated as well-known ports but are still registered and assigned to specific services by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).

These ports are commonly used for external services that users might install on a device. For instance many database services, such as Microsoft SQL Server use port 1433. Software companies frequently register a port for their applications to ensure that their software consistently uses the same port on any system.

The registration helps in manging network traffic and preventing port conflicts across different applications.

Dynamic/Private Ports (49152-65535)¶

Dynamic or private ports, also known as ephemeral ports, range from 49152 to 65535 and are typically used by client applications to send and receive data from servers, such as when a web browser, connects to a server on the internet.

These ports are dynamic because they are not fixed; rather, they can be randomly selected by the client's operating system as needed for each session. Generally used for temporary communication sessions, these ports are closed once the interaction ends. Additionally, dynamic ports can be assigned to custom server applications, often those handling short-term connections.

Browsing the Internet Example¶

The following example represents the steps taken for a web request to reach the correct destination and return the information we seek.

1. DNS Lookup¶

Computer resolves the domain name to an IP Address (e.g. 93.184.216.34 for example.com)

2. Data Encapsulation¶

Step by Step:

| Step |

|---|

| Your browser generates an HTTP request. |

The request is encapsulated with TCP, specifying the destination port 80 or 443. |

The packet includes the destination IP address 93.184.216.34. |

| On the local network, our computer uses ARP to find the MAC address of the default gateway (router). |

3. Data Transmission¶

| Step |

|---|

| The data frame is sent to the router's MAC address. |

| The router forwards the packet toward the destination IP address. |

| Intermediate routers continue forwarding the packet based on the IP address. |

4. Server Processing¶

| Step |

|---|

| The server receives the packet and directs it to the application listening on port 80. |

| The server processes the HTTP request and sends back a response following the same path in reverse. |

5. Response Transmission¶

| Step |

|---|

| The server sends the response back to the client’s temporary port, which was randomly selected by the client’s operating system at the start of the session. |

| The response follows the reverse path back through the network, being directed from router to router based on the source IP address and port information until it reaches the client. |

Exercises:¶

Q: What protocol maps IP addresses to MAC addresses?

A: ARP

Q: Which IP version uses 128-bit addressing?

A: IPv6

Q: At which layer of the OSI model do ports operate? (Format: two words)

A: Transport Layer

Q: What is the designated port number for HTTP?

A: 80

Q: What is the first step in the process of a web browsing session? (Format: two words)

A: DNS Lookup